Partners and Citizens

A Forum On Missions and Politics

Latest Articles

We live in an era where leadership training is everywhere. Books, podcasts, and conferences promise the latest framework, the newest method, the secret that will finally “move the needle.” Pastors and church leaders, in particular, are routinely targeted as prime consumers of leadership content.

And yet leadership remains in crisis.

Many people had already “followed” Jesus—right up until his words offended them or his mission threatened their dreams. In John 6, after Jesus refused to be used as a political deliverer or a bread machine, the crowd thinned fast:

“After this many of his disciples turned back and no longer walked with him.” (John 6:66)

That’s the danger Jesus is addressing in John 16. Not merely external persecution, but internal collapse—when the thing you really love gets threatened, and Jesus no longer seems worth it. So the question beneath the passage is not, “Will you face pressure?” You will. The question is: “What will hold you when you do?” Because what you love will hold you.

Everyone possesses a theology, whether they admit it or not. If you have not reflected on the source of your worldview, it is guaranteed that your theology has been shaped by the influences surrounding you. For example, children raised exclusively in Muslim communities often grow into adults with a fatalistic mindset, as that culture is grounded in determinism. During the year I lived in Bahrain, I heard the Arabic phrase “Inshalla,” meaning “If God wills it,” probably ten times a day. Conversely, a child raised in secular America often has a markedly different outlook, believing that they are the masters of their own destinies. America is obsessed with liberty and freedom, which may partly explain why many Westerners cringe at the mention of Calvinism, as it suggests that we may not be as in control of our outcomes as we wish to believe. That said, the great director Mr. Nolan undoubtedly has his own theology, and my purpose today is to explore some aspects of that worldview as reflected in the plot of Interstellar.

When I worked at Central Church in Collierville, Tennessee, I had a daily routine I came to love. After parking by the Worship Center, I’d walk straight into Central’s coffee shop and bookstore—the Crosswalk—managed by Carlene Boldizar. Without fail, she’d hand me the best cup of coffee in town: beans roasted by her husband, George, and brewed to perfection by Carlene herself.

About an hour before the event, I spotted a beat-up car slowly wandering through the parking lot near the classic show vehicles. My heart rate skyrocketed. Certain this lone assassin was seconds away from totaling someone’s prized ’68 Camaro, I locked eyes on the threat and marched heroically toward the scene—only to walk directly into a metal No Parking sign.

With only two months to breathe life into a brand-new concept—and as the only person on the planning team actually employed by Central Church—I rushed straight to work. We decided early on that football would anchor our first Gameday event, since the season launches in August and resonates deeply with our community. But the goal was never just an evening of free food, bounce houses, and football décor. Our vision was to introduce Central Church, and the warmth of her people, to the community through a shared cultural love. Grilled hot dogs and games alone wouldn’t accomplish that.

Through my research, I found that men addicted to sports often become strangers in their own homes. This essay will explore where sports obsession began historically, how modern culture intensifies it, why men are ensnared by it, what consequences follow, and finally how Scripture speaks to the problem.

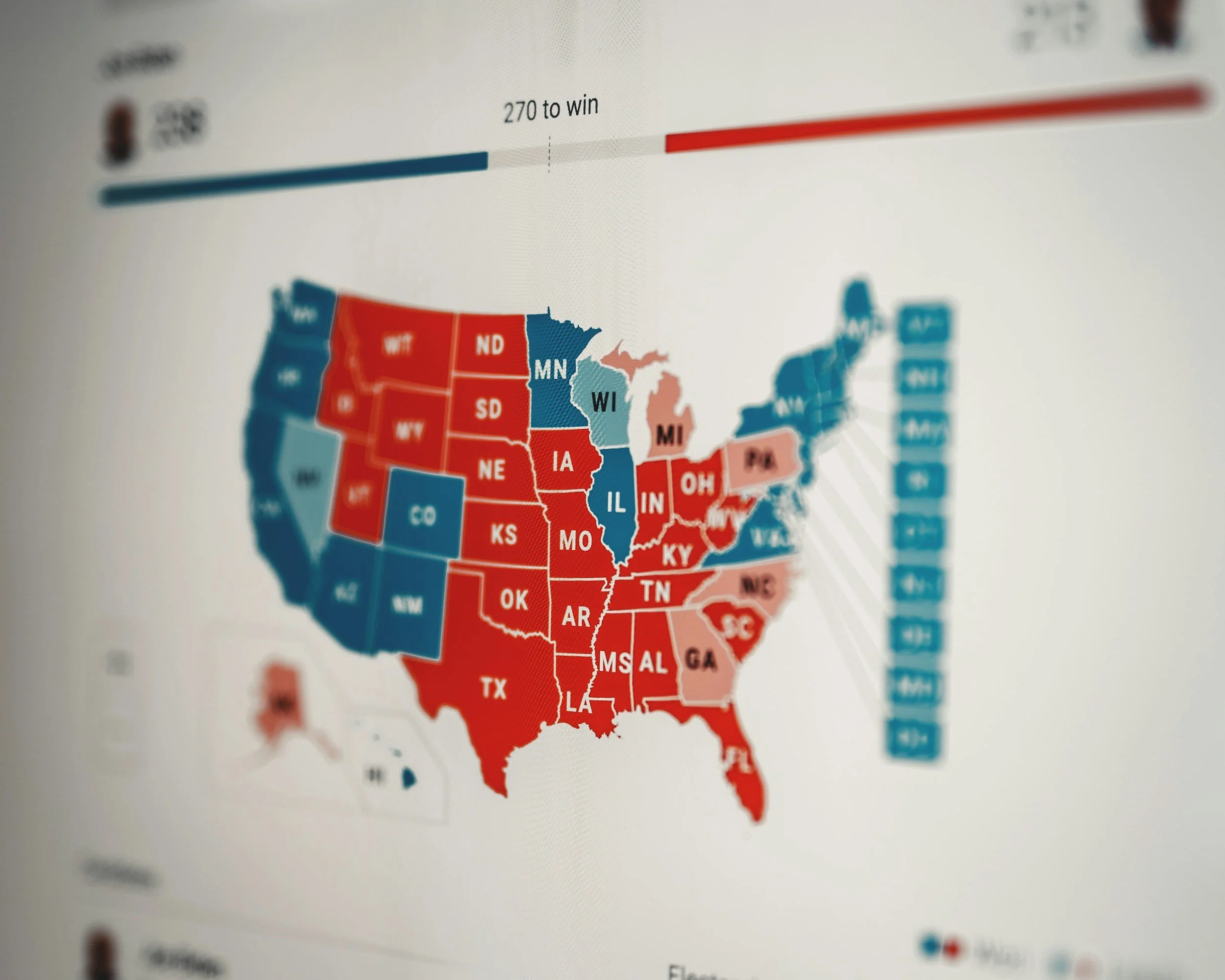

In the aftermath of the 2004 presidential election, scholars renewed their attention to the role of religion in American electoral politics. George W. Bush mobilized a sizable religious bloc in his reelection campaign against Senator John Kerry, strengthening the perception that highly religious voters tend to vote Republican while less religious voters tend to vote Democratic. This pattern became widely known as the “God Gap.” The implication was clear: if Democrats hoped to win back the White House, they would need to compete more effectively for religious voters. In 2008, Barack Obama made narrowing the “God Gap” a visible priority of his campaign.

In The Disappearing God Gap, six contributing authors analyze how religion functioned in Obama’s historic victory. The book argues that religion played a meaningful role throughout the campaign process—from both parties’ primaries through Election Day. While American public policy maintains a formal separation of church and state, the book insists that this does not mean religion and politics are separated in practice.

One of Nolan’s most compelling features, however, is easy to miss beneath the weight of plot twists, villains, and thrills: the relationship between Bruce Wayne/Batman and his butler, Alfred Pennyworth. This relationship becomes philosophically illuminating when read alongside Søren Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, written in Berlin and published in 1843 under the pseudonym Johannes de Silentio (“John the Silent”). The title, drawn from Paul’s letter to the Philippians—“continue to work out your salvation with fear and trembling” (Phil. 2:12)—signals Kierkegaard’s concern with the seriousness of faith. In a Kierkegaardian analysis of Nolan’s narrative, Bruce Wayne embodies the ethical individual who devotes himself to the universal common good, while Alfred—guardian, watchman, and provider—resembles the knight of faith, the religious individual.

When I began my role at Central Church in early 2022, I was stepping into a world that felt entirely new. I had never worked in a large evangelical church with a full team of support staff and an army of dedicated volunteers. As a part-time college pastor and cash-strapped church planter in previous seasons, “thinking big” was usually synonymous with “thinking cheaply.” Even so, I always loved dreaming up creative ways to do outreach.